The interaction of evidence, expert opinions and controversy in psychiatry

- Johanne Pereira Ribeiro

- Dec 9, 2025

- 8 min read

The case of methylphenidate hydrochloride to treat attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents

Methylphenidate has been the first-line treatment for children and adolescents with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder for more than half a century. Yet, after numerous systematic reviews, three applications to get methylphenidate on the List of Essential Medicines and three rejections by the World Health Organization, the questions remain: does it work, and how do we know?

Methylphenidate in context

For more than sixty years, methylphenidate has been the first-line pharmacological treatment for children and adolescents diagnosed with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)(1). The use of methylphenidate is widespread with well-known brand names across the world. Yet after decades of research and three rejections from the World Health Organization (WHO) of its inclusion on the Model list of Essential Medicines (2019, 2021, and 2025) one of the most prescribed psychotropic drugs in the world still lacks convincing evidence of clinically meaningful benefits at group level. It raises an important question relevant for clinicians and researchers; how do we ethically and scientifically act when data remain uncertain, for a treatment that is so deeply embedded in clinical practice?

The “proof”

The 2015 Cochrane systematic review examined 185 randomised clinical trials comparing methylphenidate with placebo or no intervention in children and adolescents with ADHD(2). The trials were numerous, yet many of them were characterised by methodological limitations. Most had unclear or high risk of bias, selective outcome reporting, and limited follow-up durations (usually less than three months). Across studies, methylphenidate showed improvements in ADHD symptom scores and general behaviour, but the certainty of the evidence was rated very low. Serious adverse events were underreported, and non-serious adverse events such as sleep problems, loss of appetite, and abdominal pain were common (2). The findings were “controversial” because they challenged long-standing clinical assumptions that had become deeply embedded in ADHD treatment practices, thus igniting substantial academic debate. Some argued that the review underestimated the drug’s efficacy or used overly strict assessment criteria (3–6). Rebuttals pointed out that if this was the best evidence we had after half a century of use, perhaps the problem was not the review but the evidence base itself (7–10).

Revisiting the evidence

In a 2021 overview, we re-examined all systematic reviews and meta-analyses published since 2013 (11). Out of 24 identified systematic reviews, only 11 were of high methodological quality according to the AMSTAR II tool. Most reported small beneficial effects, again based on low to very low certainty of evidence (11). In 2023, we updated the Cochrane review (12). The conclusion remained unchanged: methylphenidate may reduce core ADHD symptoms, but the certainty of its effect is very low. Adverse effects remain incompletely reported, and long-term outcomes from randomised clinical trials are still almost absent (12). This situation highlights a broader dilemma in psychopharmacology: a large number of studies do not equal robust evidence. When included trials are characterised by methodological shortcomings, limited duration, and selective outcome reporting, the reliability of summary effects becomes uncertain.

Rejected by the WHO - third time was not the charm

In 2018, researchers from Mount Sinai applied to include methylphenidate on the WHO’s Model List of Essential Medicines for children and adolescents with ADHD(13). The expert committee unanimously rejected the application, citing “uncertainties in the estimates of benefit” and concerns about the quality of the evidence (14). The application was resubmitted in 2020 by a new research group(15) and was again declined in 2021 (16). When a revised version, including new collaborators, was presented a third time in 2025, the WHO maintained its position (17). Three consecutive rejections are unusual and indicate that, despite extensive research, uncertainty remains about the overall effects of methylphenidate and whether the evidence is sufficient to justify its inclusion on the list.

The “polarisation”

Clinicians often report clear, sometimes striking improvements in individual patients treated with methylphenidate. Teachers and parents may describe noticeable behavioural changes within days. For them, the drug “works.” Randomised evidence, however, tells a more nuanced story. The average benefit, when measured on group-level symptom scales, appears modest and uncertain. Most trials last only a few weeks, whereas real-world treatment typically continues for years. Adverse effects are inconsistently recorded, and reporting is often incomplete.

In addition to clinical impressions, many clinicians rely on positive findings from register based studies, suggesting that methylphenidate is associated with reduced risks of accidents, criminal behaviour and the development of co-occurring disorders (18,19). Such studies might seem compelling because they reflect “real-world”-data on large populations, but they are limited by unmeasured confounding e.g. due to the lack of control over interventions. They rely on routine collected data with little insight into misclassified outcomes and without the possibility of assessing the extent or nature of missing data. Meanwhile, other register-based studies have found no evidence of a protective effect of methylphenidate on accidents, criminality, or comorbid disorders (20–22).

While many clinicians observe clear benefits in practice, and some observational studies appear to support them, systematic reviews and the WHO’s repeated rejections of methylphenidate for inclusion on the Essential Medicines List continuously highlight substantial uncertainty in the evidence base.

This gap between clinical experience observational data, and aggregated evidence is the perfect condition for disagreement and polarisation. On one side stand clinicians with the experience and belief that methylphenidate works, and that effects are self-evident; on the other, researchers emphasising that feeling convinced due to clinical experience does not constitute objective proof.

What do we mean by “work”?

The core question is not simply whether methylphenidate work, but rather what do we actually mean by “work”? If “work” means short-term reduction in teacher-rated hyperactivity scores, the answer may be yes, but with low or very low certainty. If “work” means sustained improvements in functioning, relationships, academic outcomes, or quality of life, the evidence is silent. If “work” means that the benefits outweigh harms for most children during long-term treatment, we simply do not know.

The word “work” often oversimplifies the complexity of the questions, turning uncertain and context-dependent findings into a statement of facts.

Navigating clinical uncertainty

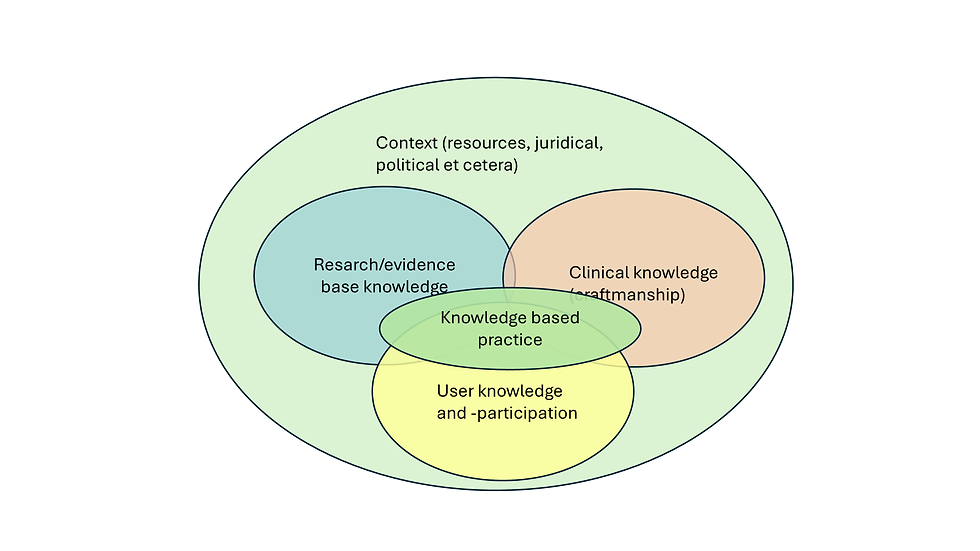

So, what are clinicians to do? Given the persistent uncertainty in the evidence base, clinicians face a challenging but important responsibility. Recognising that evidence-based practice relies not only on external evidence but also on clinical expertise and patient preferences, treatment decisions should not rest solely on the assumption that methylphenidate “works.” Instead, they should be guided by a careful, individualised assessment of each child’s needs, preferences, and response to the medication. Openly discussing both potential benefits and risks, including the gaps in long-term data is essential and clinicians should monitor outcomes systematically, remain alert to adverse effects, and consider non-pharmacological interventions alongside or before medication. In doing so, they acknowledge the limitations of the current evidence while still providing attentive, ethically grounded care to children and adolescents with ADHD. □

References

Gadoth N. Methylphenidate (Ritalin): What Makes it so Widely Prescribed During the Last 60 Years? Curr Drug ther [Internet]. 2014 Jan 31;8(3):171–80. Available from: http://www.eurekaselect.com/openurl/content.php?genre=article&issn=1574-8855&volume=8&issue=3&spage=171

Storebø OJ, Ramstad E, Krogh HB, Nilausen TD, Skoog M, Holmskov M, et al. Methylphenidate for children and adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet]. 2015 Nov 25;2016(11). Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/14651858.CD009885.pub2

Banaschewski T, Gerlach M, Becker K, Holtmann M, Döpfner M, Romanos M. Trust, but verify. The errors and misinterpretations in the Cochrane analysis by O. J. Storebo and colleagues on the efficacy and safety of methylphenidate for the treatment of children and adolescents with ADHD. https://doi.org/101024/1422-4917/a000433 [Internet]. 2016 Jul 18 [cited 2025 Oct 22];44(4):307–14. Available from: /doi/pdf/10.1024/1422-4917/a000433

Banaschewski T, Buitelaar J, Chui CSL, Coghill D, Cortese S, Simonoff E, et al. Methylphenidate for ADHD in children and adolescents: throwing the baby out with the bathwater. Evid Based Ment Heal [Internet]. 2016 Oct 21 [cited 2025 Oct 22];19(4):97–9. Available from: https://mentalhealth.bmj.com/content/19/4/97

Romanos M, Reif A, Banaschewski T. Methylphenidate for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. JAMA [Internet]. 2016 Sep 6 [cited 2025 Oct 22];316(9):994–5. Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2547744

Hoekstra PJ, Buitelaar JK. Is the evidence base of methylphenidate for children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder flawed? Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry [Internet]. 2016 Apr 1 [cited 2025 Oct 22];25(4):339–40. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00787-016-0845-2

Storebø OJ, Zwi M, Krogh HB, Moreira-Maia CR, Holmskov M, Gillies D, et al. Evidence on methylphenidate in children and adolescents with ADHD is in fact of ‘very low quality.’ Evid Based Ment Heal [Internet]. 2016 Oct 21 [cited 2025 Oct 22];19(4):100–2. Available from: https://mentalhealth.bmj.com/content/19/4/100

Storebø OJ, Simonsen E, Gluud C. Methylphenidate for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder—Reply. JAMA [Internet]. 2016 Sep 6 [cited 2025 Oct 22];316(9):995–995. Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2547750

Storebø OJ, Simonsen E, Gluud C. The evidence base of methylphenidate for children and adolescents with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder is in fact flawed. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry [Internet]. 2016 Sep 1 [cited 2025 Oct 22];25(9):1037–8. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00787-016-0855-0

Storebø OJ, Zwi M, Moreira-Maia CR, Skoog M, Camilla G, Gillies D, et al. Response to “Trust, but verify” by Banaschewski et al. https://doi.org/101024/1422-4917/a000472 [Internet]. 2016 Sep 19 [cited 2025 Oct 22];44(5):334–5. Available from: /doi/pdf/10.1024/1422-4917/a000472

Ribeiro JP, Arthur EJ, Gluud C, Simonsen E, Storebo OJ. Does Methylphenidate Work in Children and Adolescents with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder? Pediatr Rep [Internet]. 2021 Aug;13(3):434–43. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3390%2Fpediatric13030050

Storebø OJ, Storm MRO, Pereira Ribeiro J, Skoog M, Groth C, Callesen HE, et al. Methylphenidate for children and adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet]. 2023 Mar 27;2023(3). Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/14651858.CD009885.pub3

World Health Organisation. The Selection and Use of Essential Medicines The Selection and Use of Essential Medicines WHO Technical Report Series [Internet]. Geneva; 2019 [cited 2025 Oct 22]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241210300

Storebø OJ, Gluud C. Methylphenidate for ADHD rejected from the WHO Essential Medicines List due to uncertainties in benefit-harm profile. BMJ Evidence-Based Med [Internet]. 2021 Aug 1 [cited 2021 Oct 19];26(4):172–5. Available from: https://ebm.bmj.com/content/26/4/172

World Health Organization. A.21 Methylphenidate – attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder – EML and EMLc [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2025 Oct 22]. Available from: https://www.who.int/groups/expert-committee-on-selection-and-use-of-essential-medicines/23rd-expert-committee/a21-methylphenidate

Pereira Ribeiro J, Lunde C, Gluud C, Simonsen E, Storebø OJ. Methylphenidate denied access to the WHO List of Essential Medicines for the second time. BMJ Evidence-Based Med [Internet]. 2022;bmjebm-2021-111862. Available from: http://doi.org/10.1136/bmjebm-2021-111862

World Health Organization. The selection and use of essential medicines, 2025: report of the 25th WHO Expert Committee on Selection and Use of Essential Medicines, executive summary [Internet]. Geneva; 2025 [cited 2025 Oct 22]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/B09544

Zhang L, Zhu N, Sjölander A, Nourredine M, Li L, Garcia-Argibay M, et al. ADHD drug treatment and risk of suicidal behaviours, substance misuse, accidental injuries, transport accidents, and criminality: emulation of target trials. BMJ [Internet]. 2025 Aug 13;390:e083658. Available from: https://www.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/bmj-2024-083658

Ruiz-Goikoetxea M, Cortese S, Aznarez-Sanado M, Magallón S, Alvarez Zallo N, Luis EO, et al. Risk of unintentional injuries in children and adolescents with ADHD and the impact of ADHD medications: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev [Internet]. 2018 Jan;84:63–71. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0149763417306723

Widding-Havneraas T, Zachrisson HD, Markussen S, Elwert F, Lyhmann I, Chaulagain A, et al. Effect of Pharmacological Treatment of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder on Criminality. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry [Internet]. 2024 Apr;63(4):433–42. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0890856723003404

Widding-Havneraas T, Elwert F, Markussen S, Zachrisson HD, Lyhmann I, Chaulagain A, et al. Effect of ADHD medication on risk of injuries: a preference-based instrumental variable analysis. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry [Internet]. 2024 Jun 24;33(6):1987–96. Available from: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00787-023-02294-6

Lyhmann I, Widding-Havneraas T, Bjelland I, Markussen S, Elwert F, Chaulagain A, et al. Effect of pharmacological treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder on later psychiatric comorbidity: a population-based prospective long-term study. BMJ Ment Heal [Internet]. 2024 Jan;27(1):e301003. Available from: https://mentalhealth.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/bmjment-2024-301003