The neuropsychiatric paradigm of ADHD is limping– time to lift the blinders?

- Tomas Ljungberg

- Nov 26, 2025

- 15 min read

This article is based on a short lecture originally given in the Swedish Psychiatric Associations yearly meeting in Stockholm in March 2024. I have since given a similar lecture on other occasions. The article below is a summary of the main points of the lecture. My intention with the lecture was to bring into awareness and discuss some current international research important for understanding ADHD, research that is not often discussed in Sweden. Because of space limitations here, I have only included the main conclusions and the most important references. I hope that despite this, the main message will still be conveyed even though a full and balanced argumentation cannot be given.

The current Swedish explanation of ADHD

The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare has for more than 20 years promoted the narrative that ADHD is a neuropsychiatric disorder. By this they mean that the symptoms of ADHD are explained by deviating biological processes and functions in the brain. They claim that the main causal factor is genetics, which explains 75% or more of the causation. Of remaining causal factors, complications during pregnancy and/or delivery, for example premature birth, are highlighted as being the most important. Psychological or psychosocial factors, like conflicts, stress or trauma in families, economic burden, psychosocial strain, conditions in schools etc., are clearly stated as not being causal factors. Because of genetic and biological causation, ADHD is by the Swedish National Board of Health and welfare to be counted as a life-long impairment (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7).

The biological functions that are affected in ADHD are described to be (mainly) located in frontal cortex (associated with lower volumes of these areas) and basal ganglia, and the neurotransmitters dopamine and noradrenaline are explained to be hypofunctional. The deviating functions of frontal cortex and in the dopamine and noradrenaline systems affect cognitive functions in the frontal cortex, like attention, working memory and executive functions (1, 3, 4). These cognitive dysfunctions are claimed to explain the appearance of the specific symptoms observed in ADHD. The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare even explicitly explain that “ADHD and autism are disabilities that affect cognitive ability” (8), thus stating that ADHD is a disability in the brain that affects cognitive functions.

As a logical step following the conclusion that ADHD is a biological and neuropsychiatric disorder, the recommended first line treatment includes central stimulants (methylphenidate). Central stimulants increase dopamine and noradrenaline transmission in the brain and, consequently, reinstate the deficiencies characterizing the neurobiological deviations of ADHD (1, 4, 7). As ADHD is seen as a brain dysfunction with severe long-term consequences, the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare in their latest guidelines also state that suspected ADHD should be investigated and diagnosed without unnecessary delay. When diagnosed, first line treatment includes methylphenidate, and one of their quality indicators implies that a high percentage of newly diagnosed children receiving medical treatment is a high-quality medical care (7).

With this paradigmatic understanding of ADHD, it is not difficult to understand why the number of children with an ADHD diagnosis that are treated with ADHD-medications has skyrocketed in Sweden. According to their own prognosis, the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare foresee that in a near future 15% of Swedish boys in school-age (10-17 years of age) are going to be treated with ADHD-medication (9).

And all of this would be understandable if the neuropsychiatric narrative of ADHD was correct. But is it? There are an increasing number of interesting new publications accumulating that, at least I think, are very difficult to reconcile with this neuropsychiatric narrative of ADHD. Let me take just a few examples.

The youngest children in a school class are more often diagnosed with ADHD

Already 2010, the American Professor in economics, Todd E Elder, showed that in the USA, the youngest children in school classes were more often diagnosed with ADHD and treated with central stimulants. This was not dependent on birth month, as the school years were broken at different times of the year in the different states that he investigated. Independent of birth month, it was always the youngest children in the classes that more often were diagnosed with ADHD (10). His findings have been replicated in two independent media investigations here in Sweden (2015; SVT and 2023; DN), and both investigations showed that the prevalence of ADHD is approximately 30-40% higher in children born in November and December compared to children born in January and February. In a recent systematic review, the robustness of this phenomenon – now called the relative age effect – is clearly documented (11).

An interesting and deepened understanding of this phenomenon was revealed by a recent study undertaken in Great Britain. Almost 15.000 children were followed from the age of 4 up to the age of 25. The study found the same principal result, i.e. the relative age effect was present as more hyperactivity was observed in the younger children in the classes. However, they found no hyperactivity in the younger children before the start of school and normal levels of activity after the children had finished school (12). These results were interpreted to show that the increased level of activity in the youngest children in school classes – the relative age effect – was only observed during the years when the children were in school – it was context dependent. It was not something present in the child all the time, i.e. some form of anomaly of brain functions causing the hyperactivity that the children had from early life and up to adulthood.

Is ADHD always a childhood-onset neuropsychiatric disorder?

The hypothesis that onset of ADHD always is early in life, and that it is a stable condition judged to be life-long, was questioned already 2015 by results from a study from New Zeeland where 1.037 individuals were followed from the age of 3 up to the age of 38. The study found that about 6% of children and 3% of adults were diagnosed with ADHD. These figures were in line with what was the accepted prevalence for ADHD at that time. However, what the study also found was surprising – 90% of the adults with ADHD had not been diagnosed with ADHD as children, and children who have had a diagnosis, only few had ADHD as adults (13).

One of the authors of the study – Professor Luis Rohde from Brazil – has continued research in this area and have replicated the results in an own study in Brazil. Even several other research groups have reported the same principal findings. Luis Rohde has introduced the term of Late Onset or Adult-Onset ADHD, and his conclusion is that at least half of adults with a new ADHD-diagnosis did not fulfill the ADHD diagnosis criteria when they were children (14).

Is ADHD a stable and life-long condition?

The findings described above must mean that ADHD is not a stable and life-long condition and always with a child-hood onset. This notion has been supported by several other studies, and how the symptoms vary over a lifespan is today often instead discussed in terms of trajectories (14). One such trajectory is that symptoms start early in life, are so pronounced so that ADHD diagnosis criteria are fulfilled and then symptoms continue to be severe up into adulthood. According to the suggestion made by Luis Rohde, this trajectory is called persisting ADHD. Another trajectory is that the symptoms are initially severe but are decaying so much over time that an ADHD diagnosis is not relevant when the person is adult. This trajectory has been called remitting ADHD.

A third trajectory is characterized by subthreshold ADHD-symptoms during childhood, but later in life, in adolescence or as a young adult, more pronounced ADHD-symptoms are displayed, and an ADHD-diagnosis is fulfilled. This trajectory is what Luis Rohde refers to as adult onset or late-onset ADHD. Changes in life requirements, new psychosocial stressors or psychic traumas are described as casual factors that can make ADHD symptoms more severe in (early) adulthood. A fourth trajectory is characterized by ADHD-symptoms fluctuating greatly over time, from severe symptoms to subthreshold symptoms at repeated occasions (14, 15). International research today is focused on describing how large these respective trajectories are.

Are deviating cognitive functions one of the hallmarks of ADHD?

One of the hallmarks of the Swedish version of the neuropsychiatric narrative is that deviating cognitive functions are causing the ADHD-symptoms. This said, it is somewhat of a surprise that decades of research have not found any specific cognitive deviating functions that are characteristic of ADHD and that can be used for differentiating children with ADHD from normal children or, for example, from children with autism. There does not exist a definite and specific cognitive profile representative for children with ADHD (see e.g. 16, 17). Differences can be seen on some cognitive tests on mean results between groups of children with and without ADHD, but the overlap between groups is considerable. Conclusions from group means cannot therefore be used to predict if an individual child has ADHD or not. This is as difficult as to try to predict the sex of an individual child from the height of that child, even though the mean height of boys at a certain age is larger than that of girls.

Are smaller frontal cortex volumes characterizing ADHD?

Another hallmark of the Swedish version of the neuropsychiatric narrative is that there are not only functional deviations in the functions of the frontal cortex, but the frontal cortex is also envisaged to be less developed and smaller in volumes in comparison to children without ADHD. This conclusion has been reached in a selected number of earlier and smaller studies interpreted to show this, but the results are not consistent, and other studies have not been able to replicate it (18). Several researchers have also written critical articles that questioned the conclusion of a specific dysfunction in a frontal-striatal system (19).

It therefore raised much interest when several laboratories started to cooperate in a consortium to finally be able to answer the question of relative volumes of frontal cortex in ADHD. The study was published in 2019. Thirty-six sites cooperated and 2.246 subjects with ADHD were compared to 1.934 controls. This was the largest study that has ever been undertaken. The results were clear – no significant differences in the volumes of frontal cortex could be seen between individuals with ADHD and controls without ADHD (20).

Are genetic factors responsible for 75% of the causation of ADHD?

In the neuropsychiatric narrative, genetic factors are claimed to be the most important factor causing ADHD and are responsible for (at least) 75% of all causations of ADHD (1, 4, 21, 22). This conclusion has been based on twin-studies where a measure called heritability has been calculated by comparing ADHD-symptoms in mono- and dizygotic twins. There are, however, several limitations and possible sources of errors in this research. For example, not all studies have achieved this result, and there are several published studies that have only found heritabilities of 40-50% (21). For interesting reasons, all these non-confirmative studies are left out. Another criticism has been that there are no known direct relations between the mathematically calculated “heritability”, and genetics or genetic mechanisms. If genes are causing ADHD to such a prominent degree, surely one must be able to find which genes or genetic mechanisms are responsible. A lot of genetic research has therefore been directed towards finding the responsible genes.

This research has, however, not given any simple answers and can to date not give support for a 75% genetic causation. It was concluded rather early that ADHD was not caused by one or a few important candidate genes. Chromosomal syndromes, where specific genes are malformed in some way, can give rise to behavioral changes that can be diagnosed as ADHD. However, such chromosomal syndromes are too rare to be of any major importance for the causation of all ADHD. Copy number variants (CNVs, i.e. repeated gene sequences) have also been suggested to be important for the causation of ADHD. However, various CNVs shown to be of importance for ADHD are not specific for ADHD and can also be found in for example autism and schizophrenia. The same CNVs can also be found in controls without ADHD. Furthermore, they are also so rare that they can only explain a fraction of all ADHD (21, 22).

There exists no biological marker or known genetic, morphological, physiological or neuropsychological dysfunction that is characteristic of ADHD and can be used for diagnosis.

Seen in the light of these data, a lot of interest was directed towards new studies of the importance of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the causation of ADHD. SNPs are much more commonly occurring, and as other genetic mechanisms have not given a reasonable explanation for a 75% genetic background for ADHD, surely this new research must add the last piece of the puzzle. Several SNPs studies have been published but let us look at the largest study published in 2023. 38.691 subjects with ADHD and 186.843 controls were included. A total of 27 SNPs were found to be significantly associated with ADHD. Case closed, or maybe not? The interest was fading when it was found that the impact of these 27 SNPs was very limited, as they could only explain 14% of the total variation, i.e. the SNP heritability was only 0,14 (23). Thus far from the 75% or so predicted.

So, what it all ends up with is the view today that several genetic changes are associated with ADHD (a polygenetic causation), but the genetic mechanisms found are either very rare, non-specific or, if common, have a very limited impact. It has been claimed in other areas of research that SNPs can explain approximately half of the total genetic impact. So, if SNPs in ADHD can explain some 14% to maybe up to 20% of the variation, the other described genetic mechanisms could explain about the same part of the variation, i.e. approximately another 20%. Even with a liberal adding it all up, it is difficult to state that known genetic mechanisms can explain more than half of the variation. This is far from the 75% genetic causation previously proposed when heritability has been calculated from (some selected) twin studies.

The term now introduced is “missing heritability”, i.e. how come the heritability studies have found so inflated values for the importance of genetic mechanisms in ADHD. Maybe the previously neglected twin studies, only showing a heritability of 40-50%, were more correct than previously thought, and the twin studies showing a heritability of 75% are the ones that are associated with some factors causing inflated heritability estimates.

What is treated when central stimulants are given to individuals with ADHD?

Central stimulants (CS) are recommended treatments for ADHD. Medication for ADHD is also recommended on a long-term basis (for several years; 7). These recommendations are based on research showing that short-term treatments with CS cause distinct ADHD-symptom reductions. But even here, there are several important questions lifted in international research that are of importance for understanding the Swedish neuropsychiatric narrative of ADHD.

One of these questions is why are there no controlled studies (RCTs) documenting long-term effects of CS? One long-term study that has been done, the MTA-study, showed no significant effects on ADHD-symptoms at the three years follow-up (24). Apart from that, long-term controlled studies (>6 months) are lacking. Positive effects of CS assumed to be indicative of a more long-term effect, like reducing driving accidents and criminality, are based on epidemiological research and are not controlled studies (RCTs). Another question that has received research interest is what is actually happening when CS medication decreases ADHD symptoms. Are there parallel positive effects on cognitive functions and on academic achievements? Two recent articles have addressed this question.

One of these articles was published in 2023 (25). Forty adult subjects participated in a randomized double-blinded and placebo-controlled study. They were given CS or placebo and were then asked to solve various cognitive tests. The results showed that their motivation to solve cognitive tasks increased, but the quality of cognitive performance decreased. In the other study from 2022 (26), children with ADHD were randomly given CS (methylphenidate) or placebo and were observed in a classroom setting where they had to learn various new academic material. The results showed that the medication had significant effects on classroom behavior and seatwork productivity but there were no detectable effects of medication on learning academic material. So, in essence what both these studies showed is that when given CS, the motivation, the ability to focus, to sit still and to concentrate, and the effort in the performance increases. However, the cognitive performance and ability to learn did not increase.

The slogan that was lifted on a recent major international ADHD-conference because of these studies was that “Pills do not give skills”. In order for CS to also improve academic performance, schools also need to give the child relevant skills to achieve academic improvements. It is not enough to just dampen symptoms.

How valid is the neuropsychiatric paradigm of ADHD?

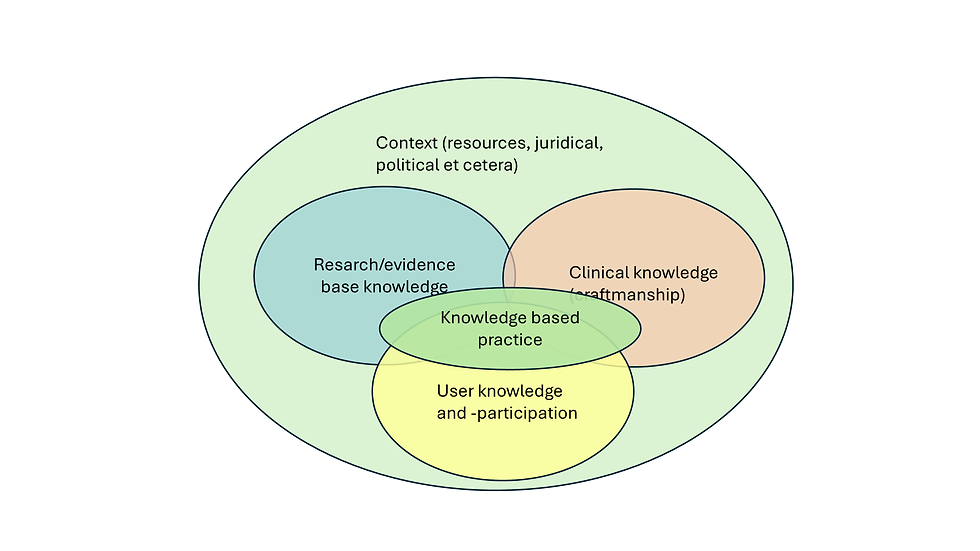

There exists no biological marker or known genetic, morphological, physiological or neuropsychological dysfunction that is characteristic of ADHD and can be used for diagnosis. ADHD is thus not a disease or disorder entity nor a category with recognizable biological characteristics. As described in DSM-5-TR (16), ADHD is characterized by specific symptoms over time that have certain consequences in everyday life. The etiology of ADHD is polygenetic and multifactorial, and there is an interplay between genetical, other biological and psychological/psychosocial factors in its causation. ADHD must therefore be seen in a psychosocial context to be correctly understood.

We contend that ADHD is not a natural entity that unfolds within an individual and can be understood independent from societal and environmental factors, but rather that ADHD as a diagnosis can better be conceptualized as a valid and pragmatically useful social construct. (27).

ADHD traits/symptoms are normally distributed, and individuals fulfilling an ADHD-diagnosis can be found in one of the more extreme tails (28). As ADHD is a dimensional phenomenon and no biological markers exist, where it is decided to put the limitation mark in the normal distribution, and state that above this mark we shall call it “ADHD”, is actually a social construct (27, 28).

The prevalence of ADHD in Sweden will soon be three times higher than what is described to be expected by DSM-5-TR. A non-negligible part of these 15% are children having problems in school because of their immaturity (being youngest in their classes). They are also treated with CS for many years, without long-term documentation of its effect. Furthermore, a non-negligible part of adults with newly diagnosed ADHD expresses more severe symptoms after exposure to trauma or psychological stressors. The paradigm promoted by the Swedish Board of Health and Welfare imply that ADHD-like symptoms in both cases are caused by inherited deviations in brain functions that should be treated with CS.

As I have shown in this article, a strict neuropsychiatric perspective is no longer scientifically valid. An update and revision of the Swedish national guidelines where current international research is taken into account is of outmost importance, not least for all children treated with CS on unscientific grounds. □

References

ADHD hos barn och vuxna, Socialstyrelsen 2002 (ISBN 91-7201-656-6).

Kort om adhd hos vuxna. Socialstyrelsen 2014-10-28

Stöd till barn, ungdomar och vuxna med adhd. Ett kunskapsstöd. Socialstyrelsen 2014-10-42.

Faraone, S et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2015 Aug 6;1:15020. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2015.20. PMID: 27189265.

Begrepp inom området psykisk hälsa. Socialstyrelsen, Version 2020.

Kortfattat om adhd hos barn och ungdomar. Socialstyrelsen 2023-5-8552

Nationella riktlinjer 2024: Adhd och autism. Socialstyrelsen 2024-3-8958

Vård som inte bör göras. Följsamhet till nationella riktlinjer. Socialstyrelsen 2023-11-8818

Diagnostik och läkemedelsbehandling vid adhd. Förekomst, trend och könsskillnader. Socialstyrelsen 2023-11-8862

Elder T. The importance of relative standards in ADHD diagnoses: evidence based on exact birth dates. J Health Econ. 2010 Sep;29(5):641-56. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2010.06.003. Epub 2010 Jun 17. PMID: 20638739; PMCID: PMC2933294.

Frisira E, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis: relative age in attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder and autism spectrum disorder. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2025 Feb;34(2):381-401. doi: 10.1007/s00787-024-02459-x. Epub 2024 May 20. PMID: 38767699; PMCID: PMC11868292.

Broughton T, et al. Relative age in the school year and risk of mental health problems in childhood, adolescence and young adulthood. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2023 Jan;64(1):185-196. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13684. Epub 2022 Aug 15. PMID: 35971653; PMCID: PMC7613948.

Moffitt TE, et al. Is Adult ADHD a Childhood-Onset Neurodevelopmental Disorder? Evidence From a Four-Decade Longitudinal Cohort Study. Am J Psychiatry. 2015 Oct;172(10):967-77. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.14101266. Epub 2015 May 22. PMID: 25998281; PMCID: PMC4591104.

Caye A, et al. Life Span Studies of ADHD-Conceptual Challenges and Predictors of Persistence and Outcome. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2016 Dec;18(12):111. doi: 10.1007/s11920-016-0750-x. PMID: 27783340; PMCID: PMC5919196.

Sibley MH, et al. Variable Patterns of Remission From ADHD in the Multimodal Treatment Study of ADHD. Am J Psychiatry. 2022 Feb;179(2):142-151. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2021.21010032. Epub 2021 Aug 13. PMID: 34384227; PMCID: PMC8810708.

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR), American Psychiatric Association, 2022.

Kofler MJ, et al. Executive function deficits in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and autism spectrum disorder. Nat Rev Psychol. 2024 Oct;3(10):701-719. doi: 10.1038/s44159-024-00350-9. Epub 2024 Aug 29. PMID: 39429646; PMCID: PMC11485171.

Seidman LJ, et al. Structural brain imaging of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2005 Jun 1;57(11):1263-72. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.11.019. Epub 2005 Jan 22. PMID: 15949998.

Castellanos FX & Proal E. Large-scale brain systems in ADHD: beyond the prefrontal-striatal model. Trends Cogn Sci. 2012 Jan;16(1):17-26. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2011.11.007. Epub 2011 Dec 12. PMID: 22169776; PMCID: PMC3272832.

Hoogman M, et al. Brain Imaging of the Cortex in ADHD: A Coordinated Analysis of Large-Scale Clinical and Population-Based Samples. Am J Psychiatry. 2019 Jul 1;176(7):531-542. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.18091033. Epub 2019 Apr 24. PMID: 31014101; PMCID: PMC6879185.

Faraone SV, Larsson H. Genetics of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2019 Apr;24(4):562-575. doi: 10.1038/s41380-018-0070-0. Epub 2018 Jun 11. PMID: 29892054; PMCID: PMC6477889.

Faraone SV, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2024 Feb 22;10(1):11. doi: 10.1038/s41572-024-00495-0. Erratum in: Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2024 Apr 15;10(1):29. doi: 10.1038/s41572-024-00518-w. PMID: 38388701.

Demontis D, et al. Genome-wide analyses of ADHD identify 27 risk loci, refine the genetic architecture and implicate several cognitive domains. Nat Genet. 2023 Feb;55(2):198-208. doi: 10.1038/s41588-022-01285-8. Epub 2023 Jan 26. Erratum in: Nat Genet. 2023 Apr;55(4):730. doi: 10.1038/s41588-023-01350-w. PMID: 36702997; PMCID: PMC10914347.

Jensen PS, et al. 3-year follow-up of the NIMH MTA study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007 Aug;46(8):989-1002. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3180686d48. PMID: 17667478.

Bowman E, et al. Not so smart? "Smart" drugs increase the level but decrease the quality of cognitive effort. Sci Adv. 2023 Jun 16;9(24):eadd4165. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.add4165. Epub 2023 Jun 14. PMID: 37315143; PMCID: PMC10266726.

Pelham WE, et al. The effect of stimulant medication on the learning of academic curricula in children with ADHD: A randomized crossover study. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2022 May;90(5):367-380. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000725. PMID: 35604744; PMCID: PMC9443328.

Banaschewski T, et al. Perspectives on ADHD in children and adolescents as a social construct amidst rising prevalence of diagnosis and medication use. Front Psychiatry. 2024 Jan 5;14:1289157. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1289157. PMID: 38250274; PMCID: PMC10796544.

Greven CU, et al. The opposite end of the attention deficit hyperactivity disorder continuum: genetic and environmental aetiologies of extremely low ADHD traits. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2016 Apr;57(4):523-31. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12475. Epub 2015 Oct 17. PMID: 26474816; PMCID: PMC4789118 (see figure B.S1. in the supporting material of this article).