When is there enough evidence?

- Nicolai Uhrenholt

- Nov 28, 2025

- 5 min read

How much evidence is enough to justify a treatment? The question sits at the fault line between science, ethics, and practice. Researchers seek methodological certainty; clinicians face patients whose needs seldom wait for consensus. Regulators demand proof before approval, while professional societies call for coherence before endorsement. Each perspective is valid, yet none alone determines when knowledge becomes action.

In psychiatry, this tension surfaces repeatedly-whether in discussions about semaglutide for antipsychotic-induced weight gain, ketamine or psilocybin for depression, or digital therapies that promise access but challenge tradition. Each innovation tests the boundary between emerging knowledge and responsible practice.

The clinician’s dilemma

For the clinician, evidence is both compass and constraint. Guidelines, meta-analyses, and regulatory approvals define the formal boundaries of what is considered safe and effective. Yet everyday psychiatry unfolds in spaces those documents rarely describe.

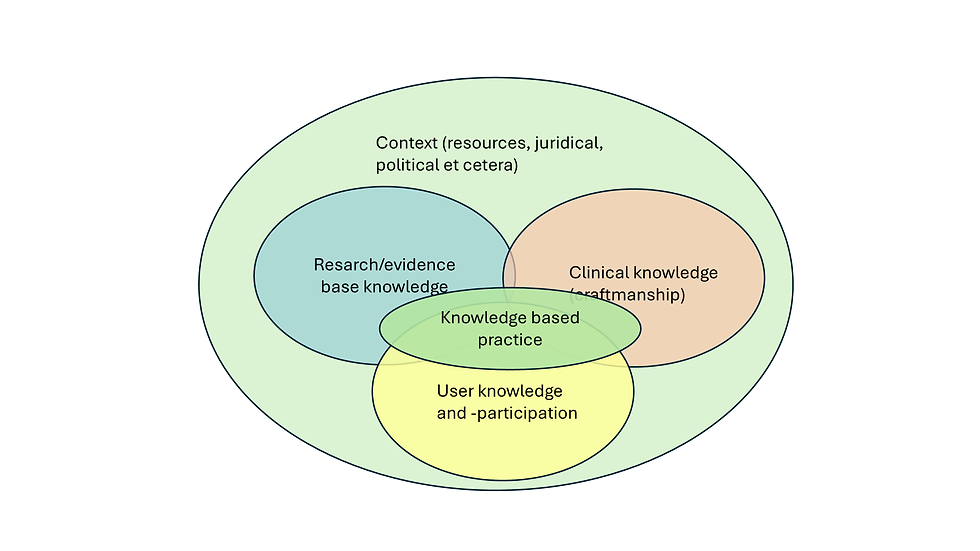

Patients differ from study populations; comorbidities, social context, and resource limitations blur the clean edges of trial data. In this reality, acting strictly by the book can be as irresponsible as ignoring evidence altogether. The art lies in interpreting incomplete knowledge-deciding when a body of research, though imperfect, is coherent enough to guide care. Clinical judgment is not a rejection of science but its necessary translation into practice.

What counts as ‘Enough’ evidence?

Over the past few decades, structured hierarchies for rating evidence have become central to what we now call evidence-based medicine (1). They were born from a legitimate desire to discipline clinical reasoning-to ensure that decisions rest on data rather than authority. Yet these hierarchies are themselves interpretive frameworks, not laws of nature. The structured ladder formalized in the 1990s gave medicine a shared grammar for judging strength of evidence (1), but it also simplified the messy interplay between methodology, mechanism, and meaning. As newer frameworks have argued, hierarchy must remain dynamic: what counts as “best evidence” depends not only on study design but on the kind of question asked and the context in which it is applied (2).

In psychiatry, this limitation is not theoretical. In Germany, up to 45% of all recommendations in published psychiatry and psychotherapy guidelines are not based on strong scientific evidence (3). This gap does not reflect negligence but the complexity of the field itself-where biological, psychological, and social mechanisms intertwine, and where controlled experimentation often yields partial or indirect insight.

“Enough” is rarely a statistical boundary. Randomized controlled trials remain the cornerstone of clinical knowledge, but they do not settle every question. Effect size, reproducibility, clinical relevance, and mechanistic plausibility all contribute to whether a finding carries weight beyond the research setting.

A small, consistent effect supported by coherent biological reasoning may justify cautious clinical use, whereas a large but isolated result may not. In psychiatry, the challenge is amplified by heterogeneity-across diagnoses, populations, and interventions. Pharmacological, psychological, and social treatments produce evidence of very different kinds, and no single metric captures them all.

What matters is the internal logic between method, mechanism, and observed outcome. “Enough evidence” is therefore not an endpoint but a negotiated state: where data, plausibility, and professional judgment align sufficiently to justify action-while remaining open to revision as knowledge evolves.

From judgment to authority

Even when evidence appears sufficient, someone must decide that it is. Between data and practice stand a series of gatekeepers-regulators, professional bodies, and institutional leaders-each translating uncertainty into policy. Their decisions define the formal boundary between innovation and established care.

Yet these layers of authority do not remove ambiguity; they redistribute it. Before approval, uncertainty belongs mainly to researchers; after licensing, it becomes the regulator’s responsibility; once guidelines are issued, it shifts again to clinicians who must interpret them for individual patients-and finally to patients themselves, who consent to treatment under imperfect knowledge.

Authority, in this sense, does not dissolve doubt-it decides who lives with it. Understanding this redistribution is central to ethical practice: it reminds us that evidence alone never determines what ought to be done; it merely defines the space in which responsible decisions must be made.

The making-and unmaking-of consensus

Consensus is often mistaken for certainty. In reality, it marks the point where enough stakeholders have agreed to act as if the evidence were settled. This agreement is indispensable for coherent practice, but it carries risk: once codified in guidelines or policy, yesterday’s provisional understanding can harden into dogma.

The rise of adaptive and platform trials (4) illustrates both the promise and the peril of this process. Such designs allow multiple treatments to be tested within a single, evolving framework, with arms added or dropped as data emerge. They accelerate learning and blur the old boundary between the research phase and clinical practice. Yet they also introduce new forms of uncertainty: delays between enrolment and outcome can dilute adaptive advantages; population drift can alter comparability; and statistical control of false positives grows complex as arms multiply (4). These designs remind us that innovation in method does not remove ambiguity; it simply moves it to new places. When the evidence stream is continuous, consensus must be continuously re-examined.

Ethics, humility, and the patient perspective

Every clinical decision carries a residue of uncertainty, and someone must bear it. For the patient, this uncertainty is not abstract but lived: a medication taken, a side effect endured, a hope recalibrated. The clinician’s task is therefore not only to interpret data but to negotiate trust-explaining what is known, what is likely, and what is still conjecture.

Ethical responsibility in this space requires neither blind caution nor reckless innovation, but humility: the willingness to act while acknowledging limits. True humility does not paralyze decision-making; it disciplines it. It demands transparency about the strength of evidence, honesty about doubt, and respect for the patient’s right to share in the reasoning, not just the outcome.

When evidence is incomplete-and it often is-trust becomes the most important clinical instrument we possess. Maintaining that trust is what turns uncertainty from a source of paralysis into a condition of responsible practice.

Conclusion - acting responsibly in uncertainty

The question of how much evidence is enough has no universal answer-and perhaps that is its value. It forces us to recognise that clinical work is conducted not at the margins of knowledge but within them. The task is not to eliminate uncertainty but to govern it: to act with discipline, proportionality, and transparency.

In psychiatry, as in all of medicine, evidence guides but never absolves. The responsibility for judgment remains personal and collective-shared between clinicians, researchers, regulators, and patients.

To act responsibly is therefore not to wait for certainty, but to make decisions that will still seem justified when the evidence inevitably changes. And that, perhaps, is the quiet discipline of psychiatry: not to find certainty, but to act wisely in its absence. □

References

Guyatt GH, Sackett DL, Sinclair JC, Hayward R, Cook DJ, Cook RJ. Users' guides to the medical literature. IX. A method for grading health care recommendations. Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 1995;274(22):1800-1804. doi:10.1001/jama.274.22.1800

Murad MH, Asi N, Alsawas M, Alahdab F. New evidence pyramid. Evid Based Med. 2016;21(4):125-127. doi:10.1136/ebmed-2016-110401

Löhrs L, Handrack M, Kopp I, et al. Evaluation of evidence grades in psychiatry and psychotherapy guidelines. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):503. Published 2020 Oct 12. doi:10.1186/s12888-020-02897-2

Saville BR, Berry SM. Efficiencies of platform clinical trials: A vision of the future. Clin Trials. 2016;13(3):358-366. doi:10.1177/1740774515626362